A blog on gardens in bloom would normally be appropriate for a readership in only one hemisphere at a time, I thought; but with global warming controlling the hosepipe I’m not so sure. Anyway, encouraged by the beautiful blooms and alluring aromas that currently accompany my morning walks through the park, I decided to clip a few extracts from musical gardens that are to be found in the catalogue.

They say that no visit to Paris is complete without a meander through one of the world’s most famous gardens, Les Tuileries. It extends for over a kilometre along the bank of the River Seine, from the Louvre to the Place de la Concorde. It was on this site that the Palace of the Tuileries once stood. Built by Catherine de’ Medici in the sixteenth century, all trace of the site was lost after the ravages of the French Revolution in 1789 and the Paris Commune insurrection of 1871. Happily, peace and tranquillity are now restored to the gardens.Let’s listen to the depiction of the Tuileries first in Ravel’s arrangement of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition (1874), in which Tuileries represents children at play and quarrelling while nursemaids gossip; then follow with part of English composer Haydn Wood’s Meditation: In the Tuileries Garden (1935), which portrays a much calmer aspect.

Mussorgsky: Tuileries (8.555924)

Wood: Meditation: In the Tuileries Garden (8.223605)

My next extract is taken from a piece written in 2004 by another English composer, Judith Bingham. Commissioned for performance at the BBC Proms that year, and titled The Secret Garden, it’s an intriguing work in which Bingham imagines what the Garden of Eden was like after Adam and Eve’s expulsion, and whose central image is the synergy that exists between plants and insects. Scored for chorus and organ, the composer introduces the work as follows:

“This is meant to be a magical and intriguing piece. It has a Christian framework with its opening and closing quotations from Genesis and Matthew, and in the second and third movements the Star of Bethlehem orchid rises like a prophecy. In this way it could be seen as a work about redemption and forgiveness. But the piece also seems to wonder whether the world is better off without humans, and that, should humans ever cease to exist, Paradise would very soon re-establish itself, in a world without blame, denial or shame. The poem, which I wrote myself, includes many Latin names of plants and moths, and this led to the subtitle of Botanical Fantasy.”Here’s the third movement, titled Vol de nuit, that sets the following text:

Tumbling down the fragrance plumes come theHawkmoths and sphinx moths, mysterious and sombre

In their nocturnal plumage. The death’s head sphinx,

Acherontia atropos, and, like a gorgeous tiny bird,

Macroglossum Stellatarum.

They navigate by scent in their longing for the

Sphingophilous flowers: Lindenia, Psychotria and the

Scented pathways of the night-shade family.

Strangest and rarest is the Star of Bethlehem

With its trailing nectar spurs, waiting, waiting for

Xanthopan morganii praedicta:

Morgan’s Sphinx.

(Organ solo: the synergy between plants and insects)

Judith Bingham: The Secret Garden (8.570346)

Back in time now, but still in England, and to music by John Jenkins (1592–1678). His long life witnessed many musical changes, from the era of William Byrd to that of Henry Purcell. He came to maturity as a composer in the 1620s, following in the footsteps of the generation that developed the genre of the consort fantasia for viols. In the Jenkins fantasia I’ve chosen, the main theme matches the folk song All in a Garden Green. Jenkins was particularly attracted to building complete pieces from a single idea, and this is a fine example, in which subtle modifications to the folk theme are combined with various subsidiary motifs.Jenkins: All in a Garden Green (8.550687)

Now to visit what one might term a ‘wild’ musical garden, as opposed to a neatly ‘cultivated’ one. It’s titled Garden of Spaces and was written by Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara (1928–2016). Rautavaara himself described the genesis of the work:

“When the Finnish Broadcasting Company proposed in 1971 that I should conduct one of my own works in a concert (the title of the concert series being ‘Conducting composers’), I had an idea for a work that could be different in each performance, created anew by each conductor. At about the same time, I visited an exhibition by architect Reima Pietilä entitled Tilatarha (Garden of Spaces), where the title ‘Regular Sets of Elements in a Semiregular Situation’ stuck in my mind. It was like something right out of the textbook of the musical avant-garde of the time, as structuralism was waning and aleatorics was making an entrance. The units of music in this piece would be regular, precisely notated, but their action, position and function in the overall structure would be free. Thus, the orchestra is divided into groups, each of which enters when, and only when, the conductor cues them in. The conductor is thus free to have these units played in any order at all, consequently or simultaneously or interleaved, creating his own structure in the process.”Here’s an extract from the piece that shows how the work was cultivated by the hands of conductor Leif Segerstam.

Rautavaara: Garden of Spaces (ODE1041-2)

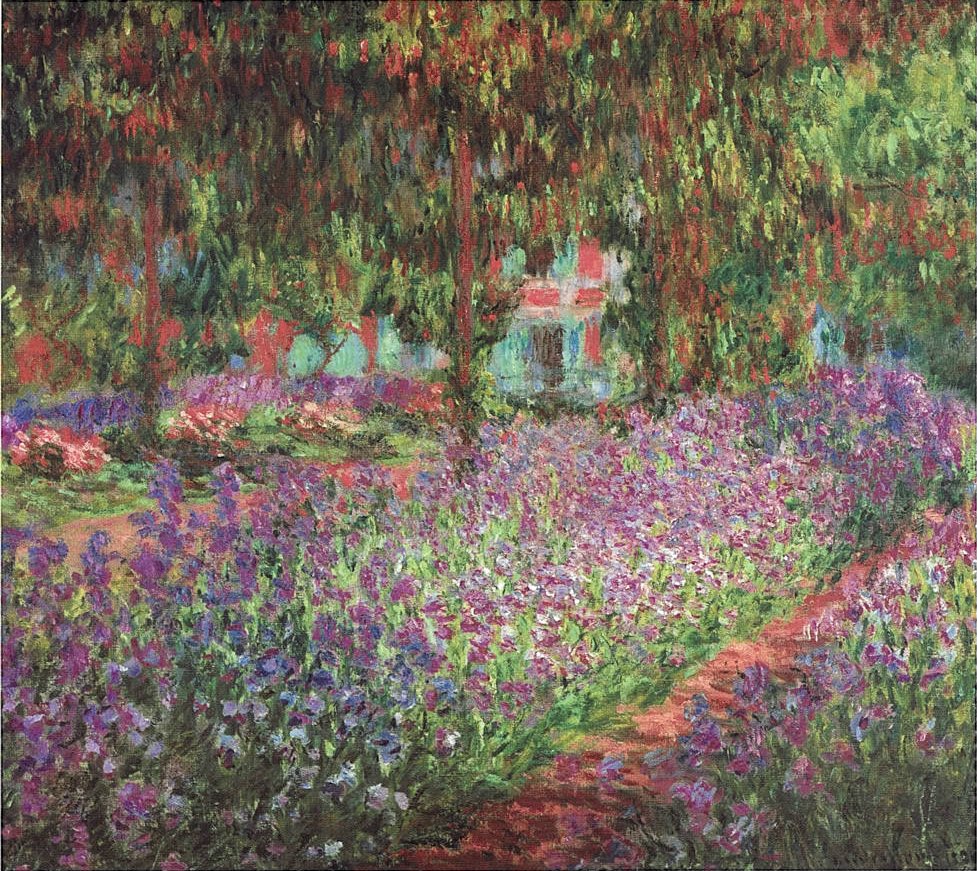

Closing the garden gate on today’s blog is Le jardin à Giverny (The Garden at Giverny) by Edward Gregson (b. 1945). It was one of the first compositions he completed during his first year as a student at London’s Royal Academy of Music in 1964. Originally a Romance for clarinet and piano, it was written for fellow student Robert Hill, later principal clarinet of the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Some 52 years later, he revisited the work, substantially reworking it for cor anglais and string quartet. The revision enhances the flowing chromatic harmonies that Gregson had discovered as a 19-year-old student in the work of composers like John Ireland (1879–1962); the result is a neat, colourful, evocative miniature for which a title borrowed from Claude Monet seems entirely appropriate – Le Jardin à Giverny.Edward Gregson: Le Jardin à Giverny (8.574223)

3 thoughts on “How does your garden go?”