I was once asked what had been the seismic developments in the history of the development of music, equivalent to scientific discoveries that had opened up entirely new vistas for society. I heard myself replying that there hadn’t been any; that from the first Neanderthal sounds on animal bones until the present day, composers had only the same basic musical ingredients to work with (commonly called the ‘elements’ of music), but had mixed them in different proportions like ever-resourceful master chefs to produce a musical smorgasbord that has continued to evolve, endure and entertain.

So, here’s a mini-challenge. I’ve chosen pieces from around the turn of each century, starting circa 1400, and invite you to compare and contrast them with reference to those elements of music that principally include tonality, tempo, texture, timbre, pitch, rhythm, dynamics, metre and form. Then you can throw in the notion of who the pieces were written for – deities, nobility, citizens, bank managers, and so on – to get the feel of what it was like to be instrumental, so to speak, in the process of musical birth. If I mixed all the extracts up, would you be able to put them in chronological order and explain your reasoning?

I live in the shadow of Canterbury Cathedral in Kent, UK. So, my first piece is by the English composer Leonel Power, who died in 1445. Although few details are known about his life, we do know that in 1423 he joined the religious fraternity of Christ Church Canterbury and almost certainly served as choirmaster of the cathedral. Here’s a performance of his Beata progenies, more redolent of an outdoor pilgrimage than a cloistered devotion.

Beata progenies unde Christus natus est;

quam gloriosa est virgo que caeli regem genuit.

Blessed is the parent from whom Christ was born;

O how glorious is the virgin who brought forth the King of heaven.

Beata progenies (8.553132)

A more widely documented musician from that same period of transition between the Mediaeval and Renaissance periods is the first truly great English composer, John Dunstable (c. 1390–1453). Writing some 20 years after his death, the musicologist Tinctoris singled him out as the transformer of the old musical style into a “new art”, the forefather of the musical Renaissance. At the same time, the poet Martin le Franc famously described how Dufay (c. 1393–1474), the eminent Franco-Flemish composer, had adopted the English manner championed by Dunstable, la contenance Angloise, that sounded so fresh and joyful to continental ears. We listen to Dunstable’s short motet Quam pulchra es. The text is taken from The Song of Solomon.

Quam pulchra es et quam decora, carissima in deliciis.

Statura tua assimilata est palme, et ubera tua botris.

Caput tuum ut Carmelus, collum tuum sicut turris eburnea.

Veni, dilecte mi, egrediamur in agrum, et videamus si

flores fructus parturierunt, si floruerunt mala Punica.

Ibi dabo tibi ubera mea.

Alleluia.

How fair and how pleasant art thou, O love, for delights!

This thy stature is like to a palm tree, and thy breasts to clusters [of grapes].

Thine head upon thee [is] like Carmel.

Thy neck [is] as a tower of ivory.

Come, my beloved, let us go forth into the field … let us see if … the tender grapes appear, [and] the pomegranates bud forth: there will I give thee my loves.

Alleluia.

Quam pulchra es (8.557341)

Moving on a generation through to the High Renaissance period we have the music of Franco-Flemish composer Josquin des Prez, whose date of birth is unknown, but whose death reliably took place in 1521. His motet Absalon fili mi was written to mourn the death of Juan Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI’s son, who was murdered in 1497. That link to the mediaeval violence associated with the Borgia family name is hardly reflected by the serenity of the music. Note how a falling melodic figure towards the end of the piece portrays the text of descendam in infernum plorans (I will go down into hell weeping).Absalon fili mi, fili mi Absalon.

Quis det ut moriar pro te,

fili mi Absalon?

Non vivam ultra,

sed descendam in infernum plorans.

Absalom my son, my son Absalom.

Who could grant me to die for you,

my son Absalom?

I shall live no longer,

but shall go down into hell weeping

Absalon fili mi (8.553428)

On now to the turn of the 17th century and to Emilio de’ Cavalieri (c. 1550–1602), a versatile musician, diplomat and courtier who is credited with the earliest surviving stage work that is set to music throughout: his Rappresentatione di Anima e di Corpo (Representation of Soul and Body), a morality presentation first performed at the Oratorio del Crocifisso in Rome in 1600. It’s regarded as the prime forerunner to the genre of opera that was soon to be born. Even his rival Jacopo Peri had to graciously allow that “Signor Emilio de’ Cavalieri, before every other that I know, with marvellous invention had introduced this new method of stage music.” Here’s Act II, Scene 4 of Cavalli’s oratorio, Chi gioia vuol (He who wants joy), featuring the allegorical figures of Pleasure, with Two Companions, Body and Soul.

Chi gioia vuol (8.554096-97)

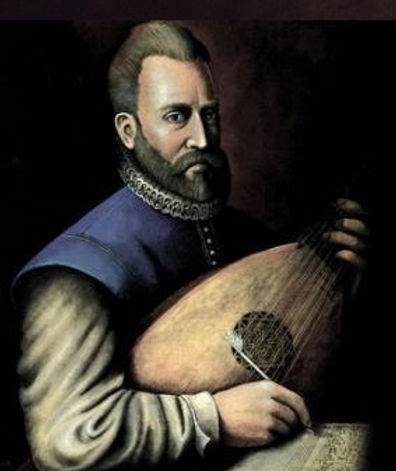

John Dowland

Source: Intankabilis / CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Flow my tears, fall from your springs,

Exil’d for ever let me mourn

Where night’s black bird her sad infamy sings,

There let me live forlorn.

Down, vain lights, shine you no more,

No nights are dark enough for those

That in despair their last fortunes deplore,

Light doth but shame disclose.

Never may my woes be relieved,

Since pity is fled,

And tears, and sighs, and groans, my weary days

Of all joys have deprived.

From the highest spire of contentment,

My fortune is thrown.

And fear, and grief, and pain for my deserts

Are my hopes since hope is gone.

Hark, you shadows that in darkness dwell,

Learn to contemn light,

Happy, happy they that in hell

Feel not the world’s despite.

Flow my tears (8.553381)

With the advantage of having actual instruments that have survived the ravages of time, we know pretty well how historic instruments sounded, but conventions of performance practice on such instruments were only infrequently written down. This was especially true of the Baroque period which made great use of improvised ornamentation of the printed score. C.P.E. Bach (1714–1788) prefaced one of his publications as follows: “It is indispensable nowadays to ornament repeats. One expects it of every performer … Almost every thought is expected to be altered in the repeat.”Dating from 1700, here’s part of Arcangelo Correlli’s Sonata IX in A major for violin and continuo. It’s exceptional in that we also have a full set of ornaments by Corelli’s pupil Francesco Geminiani with the repeats notated in full, clearly exemplifying what was expected of a performer’s skill in embellishment. It also suggests a growing equal respect for both composer and performer. Here’s the first movement.

Sonata IX in A major for violin and continuo (8.557799)

I wanted to pair that example of secular music with an example used for sacred purposes. Unlikely as it may seem, we have a set of variations on a chorale for organ written by a 15-year-old Johann Sebastian Bach to fill the slot. At the time, Bach was a student at the Michaeilisschule in Lüneberg. I would love to know what his teachers might have said of such an achievement over a flagon of ale after school was finished. Here are the final two variations of the teenage Bach’s Partite diverse sopra Christ, der du bist der helle Tag, BWV 755.Partite diverse sopra Christ, der du bist der helle Tag (8.553134)

Adalbert Gyrowetz

Source: Bwag at German Wikipedia / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Here’s the second movement of Gyrowetz’s Divertissement in A Major, Op. 50, for piano, flute and cello, first published c. 1800.

Divertissement in A Major, Op. 50 (C10398)

A quick snapshot now of the music of German-born composer Simon Mayr (1763–1845). It wasn’t until the rise of Gioachino Rossini that Mayr’s reputation for being the period’s most successful operatic composer began to be challenged. Mayr also wrote some 600 works for use in church. If you didn’t have the words before you, would you think the following music, written c. 1800, was to be delivered from the choir stalls, or enjoyed from the opera stalls?Regina coeli laetare, alleluja:

Quia quem meruisti portare, alleluja:

Resurrexit, sicut dixit, alleluja:

Ora pro nobis Deum, alleluja.

Queen of Heaven rejoice, alleluia.

For he whom thou wast worthy to bear, alleluia:

Has risen, as he said, alleluia:

Pray for us to God, alleluia.

Regina coeli (8.573909)

A century on, and definitely in the opera stalls, here’s an excerpt from Tosca, written in 1900 by Italian composer Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924), to compare and contrast with Mayr’s composing style. Tosca, a famous singer, is pleading for the life of her lover Cavaradossi, who has been captured by the chief of police. The policeman offers to spare Cavaradossi’s life only in exchange for sexual favours from her. In this aria, Vissi d’arte (I lived for art), Tosca wonders why God should punish her so cruelly, when all she has ever wanted was to live for art and love.Vissi d’arte (8.578188)

Magnus Lindberg

Source: Laivakoira2015 / CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Jubilees I. quarter note = 96 (8.570542)

Jubilees V. quarter note = 162 (8.570542)

We end in a more contemplative mood that might give space to imagine what our music scene will be like in the year 2100. It’s by another Finnish composer, Einojuhani Rautavaara, who died in 2016. Scored for string orchestra and completed in 2000, it’s titled Adagio Celeste. Here’s how Rautavaara himself introduced the work:“Adagio Celeste was prompted – like so many of my works – by a bit of text, in this case verses by Lassi Nummi written in 1982. I believe that the poem itself can say more about the music than the twelve-tone row upon which it is built.”

Then, that night, when you want to love me in the

deep of night,

wake me.

Our sheets are cool, white

like the snow outside in the twilit landscape.

I may have been waiting, may be tired of waiting,

come.

Do not grow petrified, supporting the world, like a black tree

standing alone,

come. Wake me. Let me wake

through old age and death, and wake yourself,

come like the snow, join us

to the communion of the world.

Adagio Celeste (ODE1064-5)

I suspect you mean ‘noughties’ – i.e. pertaining to (the years) nought, rather than to anything naughty.

And I would have thought that, at least in the latter half of the 20th C, there were many composers who did something rather less conservative than what you offer here, whose approach to “tonality, tempo, texture, timbre, pitch, rhythm, dynamics, metre and form” offer perhaps exactly that “seismic development” you mention.