When I was a teenager, I would occasionally try and bash through Poulenc’s Thème varié on my long-suffering upright piano. I loved the lilt of the original theme on which the variations are based. Here it is:

Thème (8.553931)

Francis Poulenc

Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France / Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Sarcastique (8.553931)

Ironique (8.553931)

Volubile (8.553931)

The rest of this blog, then, will offer a selection of what I’ll call examples of temperaments in music. We learn that there are fundamentally Four Temperaments shaping our characters: The Choleric, The Sanguine, The Phlegmatic and The Melancholy. There are two noted works that are actually titled ‘The Four Temperaments’ and ascribe their four movements accordingly. More of those later.

First, I’ve chosen music by American composer Dan Welcher (b. 1948). His String Quartet No. 1 was commissioned in 1987 by the National Endowment for the Arts for the Cleveland Quartet. The composer explains that “I worked the piece out into a four-movement format, and devised a quasi-program of moods and textures to provide contrast and change. The result is a diversified work that is, by turns, abrasive, melancholy, highly tragic, soothing, darkly comic, and victorious. The first movement is marked ‘Harsh, angry’, and pits the solo cello against the other three instruments as a kind of lone fighter against a machine-made enemy.”

Here’s how that choleric movement opens.

Harsh, angry (8.559384)

Here’s another expression of the choleric in the first movement of Leonardo Balada’s Caprichos No. 6 for clarinet and piano. Born in 1933 in Spain, Balada studied first in Barcelona before moving to settle in the United States. The clarinettist on our recording, Ivan Ivanov, was impressed to note Balada’s association with surrealist artist Salvador Dali, who endorsed the composer with a suitably eccentric comment: “This is to certify that I consider the young composer, Mr Leonardo Balada, to possess a remarkable talent!”How remarkable does Balada’s portrayal of Enojo (Anger) sound to you? Perhaps more tetchy than choleric?

Enojo (8.579056)

Clinching a sanguine, cheerfully optimistic musical mood might not seem a huge challenge, but it’s worth remembering that instrumental pieces capable of making one laugh out loud are few and far between. For my sanguine music, I’ve chosen a piece by Belgian composer Marcel Poot (1901–1988), his Vrolijke Ouverture (Cheerful Overture). Poot dedicated the piece to his teacher Paul Dukas, with whom he’d studied in Paris in the 1930s; it became very popular and helped him to become known internationally. If you’re downhearted while reading this post (surely not!), maybe it’ll help gee you up.Vrolijke Ouverture (8.223775)

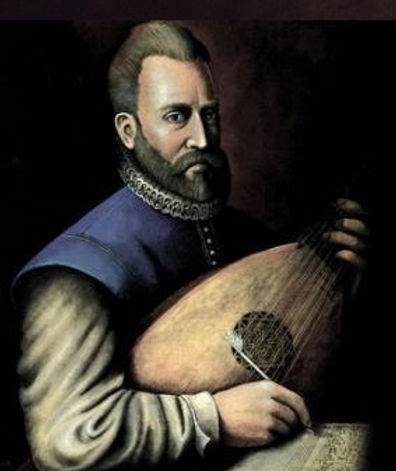

John Dowland

Source: Unknown / CC BY-SA 4.0Wikimedia Commons

Melancholy Galliard (8.553381)

Finally to what must be the most difficult of temperaments to achieve in sound, that of a phlegmatic, self-possessed, apathetic soul.

Danish composer Carl Nielsen (1865–1931) got the idea of writing a symphony based on the Four Humours after seeing a primitive peasant painting in a village inn which chimed with his own particular interest at the time in characterisation, seeing another character from the inside. The Four Humours of early medicine are the four liquids in the human body – yellow bile, phlegm, black bile and blood – a preponderance of any one of which will give rise to a temperament that is choleric, phlegmatic, melancholic or sanguine.

Nielsen’s Second Symphony ‘The Four Temperaments’ takes these characterisations as its template. It premiered in 1902 at a Danish Concert Society event in Copenhagen, with the composer himself conducting. The choleric first movement is followed by the phlegmatic, slower second. But how to cast the unemotionally stolid in musical terms? Nielsen explained that he imagined here a young man of seventeen or eighteen, a trial to his teachers, idle in his lessons, but not to be scolded. His nature leads him to the countryside, where birds sing, fish glide through the water and the sun shines, all depicted in a mood remote from energy or strong feeling.

II. Allegro comodo e flemmatico (SWR19120CD)

Paul Hindemith (1895–1963) is the other composer to have written a work titled ‘The 4 Temperaments’, in 1940, so I thought we would listen to his interpretation of ‘Phlegmatic’ to end this blog. Hindemith’s work is a ballet score for solo piano and strings and is cast in five sections: the first is a tri-partite theme on which the following four present variations reflecting the individual temperaments. Each follows a similar structure: a section for strings; dialogue between solo piano and orchestra; a siciliano for solo violin. Here’s the third variation, Phlegmatisch, in a performance by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Hindemith himself.Variation 3: Phlegmatisch (9.81122)

4 thoughts on “From bile to bravura. Musical temperaments.”