It’s Norway that comes under the spotlight this week in our Nordic composers survey. Iceland + Sweden and Denmark featured in the first two instalments; Finland will take the finale spot. The seven Norwegian composers in this chapter will be heard in chronological order, with one exception.

Ole Bull (1810–1880) was the first Norwegian musician to put his country on the map. Known as The Nordic Paganini, he was celebrated as one of the world’s great violin virtuosos, playing thousands of concerts in Europe and America over a span of almost half a century. As late as 1879, the year before he died, he was playing to a full house in Vienna’s prestigious Musikverein. Like other virtuoso musicians of the time, it was his own music that he mostly performed, aiming to impress audiences with his dazzling technique.

Bull put his skill as an improviser to good use when using folk melodies from the countries he visited as the basis of a composition. Los Recuerdos de Habana (Memories of Havana) for violin and orchestra is a good example of how such pieces were put together. It’s one of the earliest examples of the use of Creole/Cuban melodies in classical music (Bull visited Cuba in 1844). The score and solo part are lost, but a complete set of orchestral parts survives. Using these as his starting-point, Henning Kraggerud – the performer on our recording – adapted the habanera melodies and composed the variations and final coda. The resultant format is a potpourri of contrasting sections which we join part-way through the work.

Los Recuerdos de Habana (8.572827)

Johann Svendsen

Source: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

In 1859, while still a teenager, the future conductor and composer Johann Svendsen (1840–1911) met Ole Bull, whose encouragement, by the way, had also set a young Edvard Grieg on a successful career path. When he was 23, Svendsen received a royally-sponsored scholarship to enable him to study violin in Leipzig. He also used his time there to nurture a growing interest in composition. This led to the completion of his Symphony No. 1 in D major, Op. 4 in 1867, a work that Grieg later described as showing scintillating genius, superb national feeling and really brilliant handling of an orchestra; “everything”, Grieg continued, “had my fullest sympathy and forced itself on me with power that could not be resisted.” The experience led Grieg to withdraw his own symphony from further performance and to write on the score the injunction, obeyed until relatively recently: “Must never be performed.”

You can judge for yourself whether Grieg’s admiration for Svendsen’s work was understandable by listening to the third movement.

Symphony No. 1 (8.553898)

Some 25 years younger than Svendsen, Johan Halvorsen (1864–1935) was one of Norway’s most talented violinists and an internationally renowned conductor and composer. From 1899 to 1919, he directed Norway’s largest professional symphony orchestra, which then numbered 43 musicians.

In his late twenties, Halvorsen started to compose in earnest; he went on to complete more than 170 works. In 1907 he mentioned in several newspaper interviews that he was “at the moment … working on a violin concerto”. The world of Norwegian music eagerly anticipated the work’s premiere but, for whatever the real reason, Halvorsen refused to perform it in the spring of 1908, allegedly because he was nervous about how it would be received by the critics. The premiere did, however, receive its premiere in 1909, albeit in the Netherlands. The soloist was the Canadian violinist Kathleen Parlow, who told a Norwegian newspaper: “I admire Grieg and Sinding and Halvorsen. I have come here for the sole purpose of playing Halvorsen’s new concerto. It’s very interesting to perform, and also tremendously beautiful. I think it will catch on, but it’s never possible to know that for sure in advance.”

The audience, however, were unequivocal about both composer and soloist, the newspaper reporting that “Both of them were called back 8–10 times, and Halvorsen thanked Miss Parlow with a gallant kiss on the hand.” The score and parts for the work were subsequently lost, and rediscovered only in 2015 in the archive of that original soloist. Here’s part of the second movement.

Violin Concerto (8.573738)

Christian Sinding (1856–1941), a contemporary of Halvorsen, is possibly best remembered today by ambitious amateur pianists for his Rustle of Spring. He was a more important figure in the music of Norway, however, than this might suggest; in his time, he was arguably second only to Grieg. Trained in Leipzig, he fell under the influence of Liszt and Wagner, producing a large quantity of music that enjoyed contemporary popularity. Unlike others, Sinding tried to support himself purely from income derived from his compositions, taking on no other commitments, such as performing, writing or teaching. This frequently required composing to order, particularly piano works. Sinding himself even referred to this as his “piano work conveyor belt.”

Although his large output spanned many genres, it became clear early on that Sinding enjoyed a special relationship with text as a means of artistic expression, something which resulted in more than 250 songs, composed throughout his career. Here’s one of his later songs, Den sorte vin (The Dark Wine), Op. 128, No. 3.

Den sorte vin (8.553905)

Geirr Tveitt (1908–1981) was one of the most individual and prolific of Norway’s 20th-century composers, a leading figure known throughout his musical life as a composer, pianist and teacher. He was captivated as a teenager by local songs and especially by the Hardanger fiddle, the decorated folk violin of western Norway, with sympathetic strings below the fingerboard. During the Second World War, Tveitt collected over a thousand folk-tunes which he incorporated into hundreds of his works.

A decade before his death, Tveitt suffered a terrible blow when both his home and most of his music were destroyed by fire. Thanks to the efforts of his family and fellow musicians, however, Tveitt’s vivid sound world is being rekindled in recent recordings. He wrote five piano concertos, though only the last was published. Tveitt himself was the soloist in a performance of the work in Paris in 1954; the same concert saw him also performing both the Brahms and Tchaikovsky First Piano Concertos! Here’s the second movement of his own Fifth Piano Concerto, titled Danse aux campanules bleus.

Danse aux campanules bleus (8.555077)

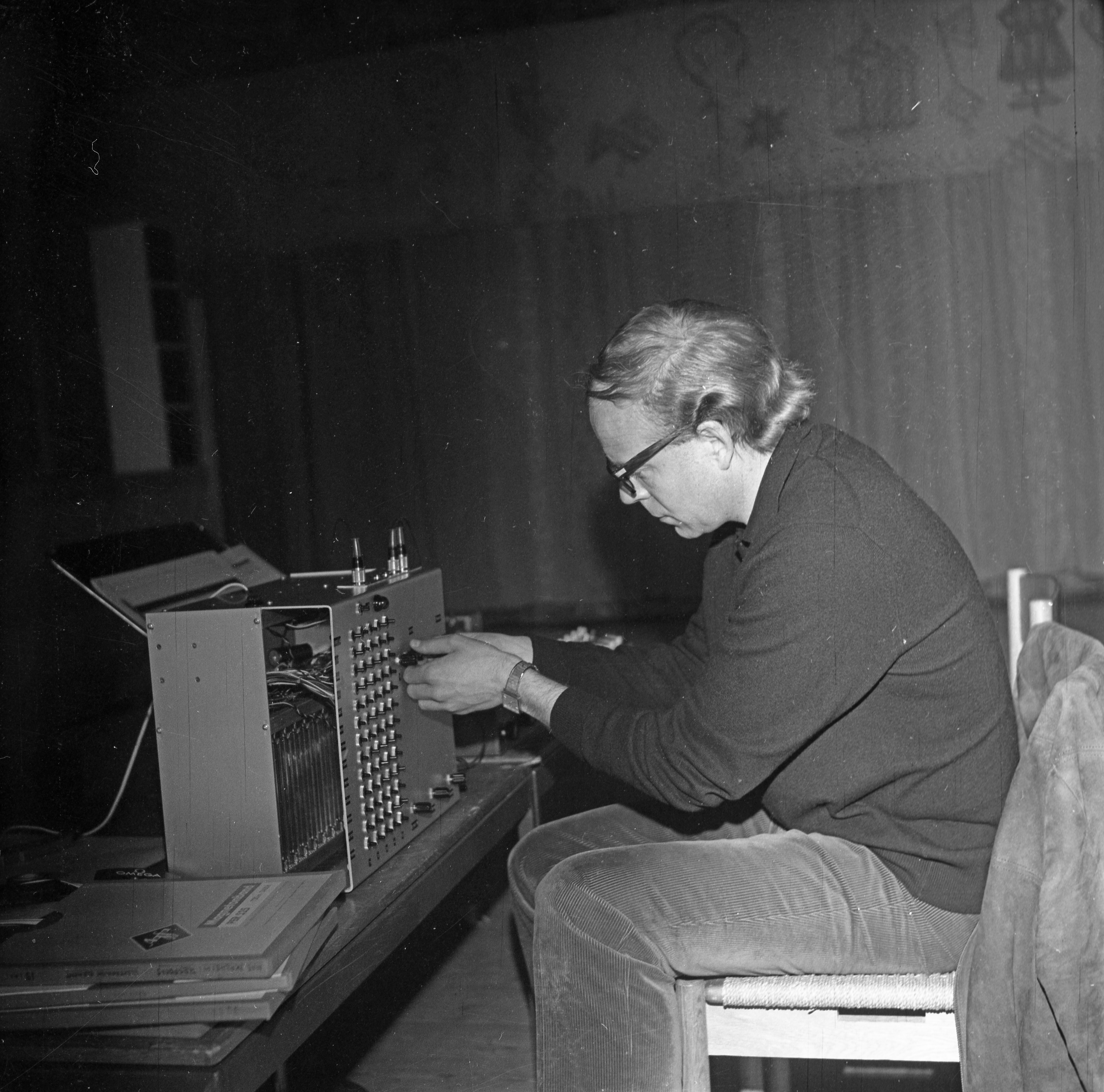

Arne Nordheim

Source: Municipal Archives of Trondheim / CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Arne Nordheim (1931–2010), the leading Norwegian composer of his generation, studied first at the conservatory in Oslo before moving to Copenhagen, where the composer Vagn Holmboe introduced him to the compositional techniques of Bartók. A visit to Paris in 1955 brought him experience of electronic music, and after further study in Stockholm, where he met György Ligeti, he was able to pioneer new techniques in his native Norway, a country that musically had remained generally conservative in taste.

His 3-movement Rendezvous, originally a string quartet written in 1956, was revised by Nordheim for string orchestra in 1986, with the new title suggesting a meeting with his younger self. Nordheim was initially influenced by Sibelius and, still more, by Mahler, and then by Bartók’s string quartets, and these influences are reflected in Rendezvous. Here’s the second movement, Intermezzo, in the arrangement for string orchestra.

Intermezzo (8.572441)

Of course, Edvard Grieg (1843–1907) remains Norway’s most famous composer. Works from his output are so comparatively well-known to music lovers, however, that I decided to lightly pass over him for this blog. Except that I thought you might like to hear an extract from his C minor Symphony, completed in 1864, on which he slapped that ‘never-to-be-performed’ notice after hearing Svensen’s First Symphony, described earlier (his ban was eventually ignored in the early 1980s). Was he right to have been so bashful about the work? You can decide for yourself as we play out with the symphony’s fourth and final movement.

Symphony in C minor (8.557991)