This is the second instalment in our alphabetical sifting through composers whose profiles are sadly more obscure than their quality compositions often deserve. Our selection focuses on surnames beginning respectively with F, G, H, I and J.

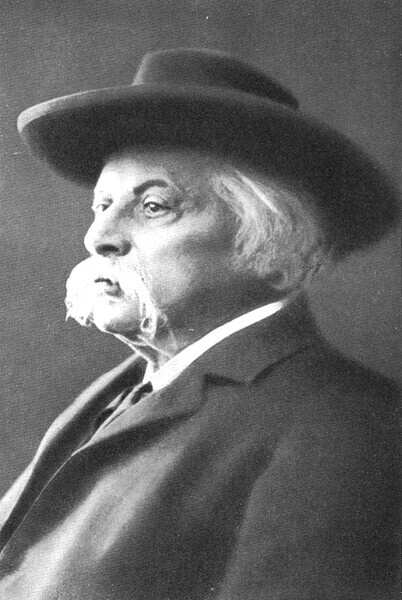

Arthur Foote

Source: Unknown Author / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The style he established in his earliest works lasted for the rest of his life: “ … always thoroughly lyrical, with broad and stately melodies; romantic in rhapsodic moods; and classical in structure, a reflection of his life-long adoration of Brahms and Wagner.” (David Ewen) He left behind 73 numbered works and 130 unnumbered compositions, from which I’ve chosen his Piano Quintet in A minor, Op. 38, which he composed in 1897. Here’s the rondo-finale.

Piano Quintet in A minor (8.559009)

Karl Goldmark

Source: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

I’ve chosen his Violin Concerto to give a taste of his musical style, which might be seen in this work as a bridge between the Mendelssohn and Brahms violin concertos. Written in 1877, it throws up an occasional reminiscence of the former, but it has many hallmarks of a later style, including the increased technical demands made on the soloist. Here’s the vivacious finale, which we join at the point of the soloist’s cadenza.

Violin Concerto (8.553579)

Fini Henriques

Source: Vilhelm Hammershøi / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

A relatively prolific composer, Henriques showed in many of his works a fondness for children, for whom he composed a number of pieces. But as he had a reputation for delivering gripping and impressive performances as a soloist, I’ve chosen a piece for violin solo and orchestra titled Romance.

Romance (8.554977)

Pedro Itturalde

Source: Ministry of the Presidency. Government of Spain / Attribution via Wikimedia Commons and La Moncloa

Czardas (8.557454)

We end with a piece of British light music that is less vigorous but equally engaging. Archibald Joyce was born in London in 1873. He studied violin and piano as a boy and soon put that ability to a practical and lucrative use by playing at dancing academies. Joyce played in various dance-bands from his teenage years onwards, occasionally travelling on cruise ships, but by 1909 he was still not sure whether his future lay in the theatre’s music hall or the ballroom’s dance events. It wasn’t long, however, before the popularity of the dance orchestra he had formed made any indecision disappear. By the early 1900s his compositions began to blossom, as did the demand for his players. They would travel to stately homes, large hotels, anywhere that required music for dancing, and Joyce soon became known as The English Waltz King.

The title of the waltz A Thousand Kisses came as a result of a chance remark by a friend of Joyce’s, at seeing a beautiful woman coming into the room: ’What a lovely girl! — she’s worth a thousand kisses’, a phrase that inspired Joyce to write this waltz in 1910. Whether the lady was the Miss Madge Slowburn to whom it is dedicated is not known. The waltz, however, was obviously familiar enough to Charlie Chaplin for him to incorporate it into a subsequent music soundtrack to his 1925 silent classic, The Gold Rush, in the saloon dance scene.

A Thousand Kisses (8.223694)

2 thoughts on “Musical discoveries F–J”